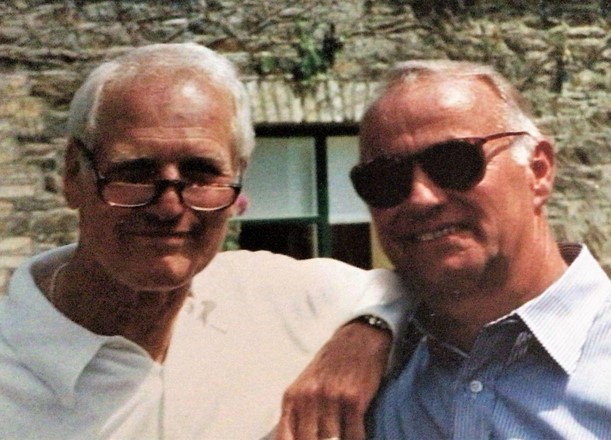

When Bob Forrester succeeded Paul Newman as Chief Executive Officer of Newman’s Own, he had a plateful of urgent issues needing to be addressed. Paul Newman was the Founder of Newman’s Own and for 26 years its only CEO. By the time of Paul Newman’s passing, his eponymous food company, Newman’s Own Inc., was a successful business admired for its founding commitment to donate 100% of profits to charity.

In the early years, this charitable commitment was a factor in Newman’s Own success, but what truly propelled the business was the mega-celebrity of its founder, Paul Newman, and the trust and respect people had for him. Paul Newman and the Newman’s Own brand were inextricably linked, and with the passing of Paul Newman, many doubted that Newman’s Own could survive without him. This over-reliance on Paul Newman was also reflected in the fact that Newman’s Own had not developed the type of planning, management financial, and leadership infrastructure needed to make it on its own.

Additionally, there were several dire threats unique to Newman’s Own, which were certain to arise once Paul was no longer here. At the top of this list was the requirement that Newman’s Own break itself up within five years i.e., go out of business as it was when Paul Newman was alive. This was due to an unintended consequence of an old tax law, and the only solution was to get a new tax law passed. This doomsday clock started ticking when Bob Forrester became CEO of Newman’s Own. (1)

Bob’s first priority, however, was to assure employees, customers, suppliers, business partners, and key grantees that he was committed to running Newman’s Own based on the values which had been laid down by Paul Newman and were at the heart of the Newman’s Own brand. Concurrently he set about assessing the strengths and weaknesses of Newman’s Own and began to put into place the most essential pillars for building a successful business operation, such as statements of policies for all functions, upgraded financial controls, basic systems support, and the recruitment of a seasoned management team.

By the spring of 2009, he was able to begin to turn his attention to the effort of trying to get a new law passed. Getting a new tax law is one of the most challenging types of legislation to get passed even in the best of times, and these were hardly the best of times for getting any legislation passed. Congress was increasingly a place of conflict and stalled legislation. The quest for Bob would be daunting, and he knew the odds were against him. The only way he could hope to be successful was to get strong bi-partisan Congressional leadership behind him. This would take developing a case supporting the new law, which was substantive, compelling, nonpartisan, one which would be seen as good public policy.

As Bob Forrester reflected, “ I knew there were red flags we needed to avoid even the appearance of being possible, and beyond that, it was important to me as a person representing the nonprofit sector, and as a taxpayer myself, that this be a good law the only purpose of which was to serve the common good, and not leave open doors for abuse. A tall order, but I felt that those who believed in Newman’s Own deserved to expect nothing less.”

One example of a red flag was that the proposed legislation not just be special legislation only benefitting Newman’s Own, i.e., an “earmark.” Thanks to Bob’s career of working in the philanthropic sector, he was aware of others who were interested in emulating the Newman’s Own commitment of donating 100% of profits to charity. There were no established reference sources for identifying such philanthropic business enterprises, but Bob was able to turn to his extensive network of contacts to begin an informal search for such businesses. His early inquires identified over 25 such businesses. There were several craft breweries, a few restaurants and cafes, a tea purveyor, a coffee purveyor, a large consulting firm, an online animal prescription service, a chocolate maker, an eyeglass store, and more. These businesses were scattered throughout the country; some were started by young, passionate, purpose-driven individuals with little if any business experience. Others were founded and run by successful business entrepreneurs who wanted to give back and felt doing so through an operating business was the best way to go. They were an eclectic group which reflected the very fabric of American small businesses and were bound together by a commitment to donate all profits to charity. It was safe to assume if an informal search produced this number, then more were out there.

Bob next looked to the future for such philanthropic enterprises, what a new tax law might do to encourage and support the further development of Philanthropic Enterprises, and what this might mean to the economy. An initial university base, independent study concluded that there was a rising tide of interest among undergraduate and graduate students in combining an operating business with a philanthropic purpose. The legislation would be a significant encouragement to those considering this course. Conversely, without such legislation, the further development of these types of businesses would not likely go anywhere.

A second study was done in 2016/17 and concluded that with a new law:

- Growth in philanthropic enterprises would jump to over 500 over ten years

- Through direct and indirect employment, philanthropic enterprises would add 47,500 jobs

- Total direct and indirect contribution to the economy would equal $50.6 billion

- Total contributions to federal, state, and local taxes would be $7.2 billion (2)

Shortly after the Philanthropic Enterprise Act was signed into law on February 9, 2018, Bob Forrester was contacted by the CEO of a 160-year-old company in the Midwest, who called to thank him for his efforts. She told Bob that the new law was the answer to their desire to keep a business presence in their community while at the same time being able to donate 100% of their profits to charity. They had converted a significant part of their business enterprise into an independent Philanthropic Enterprise like Newman’s Own, thus becoming the first existing business to become a Philanthropic Enterprise.

(1) Under extenuating circumstances, the IRS is empowered to make a one-time extension to the 5-year requirement. Bob successfully argued the case for such an extension, and the new break-up date was set for November 2018.

(2) Baseline estimates using 2016 dollars